A squirt gun would never be mistaken for a real gun, right? Dive into the thought-provoking world of Water. Gun. Argument and challenge what we choose to believe. A thought provoking and powerful piece in a docu-theatre style.

Set Design: How to cut a big musical down to size

Episode 94: Set Design: How to cut a big musical down to size

Set Designer Sean Martin talks about how high schools can put on a big musical without breaking the bank with set design.

Show Notes

- Contact Sean at: sean@joey-aristophanes.com

- Practical Technical Theatre DVD Series

“Set design for Fiddler on the Roof”

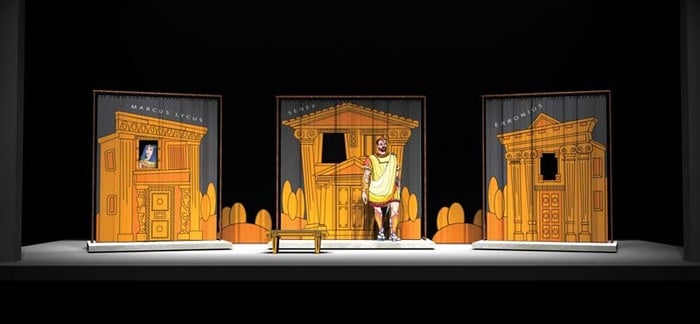

“Set design for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”

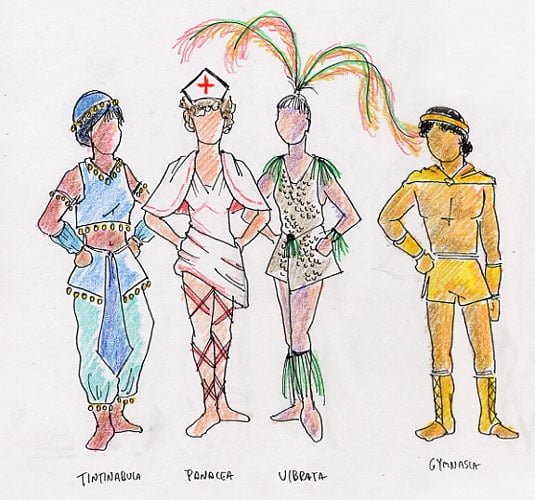

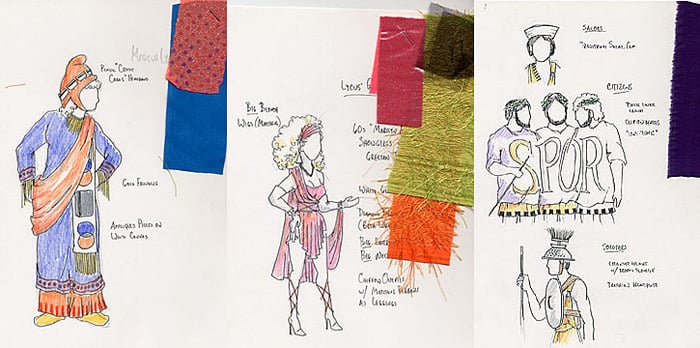

“Costume sketch for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”

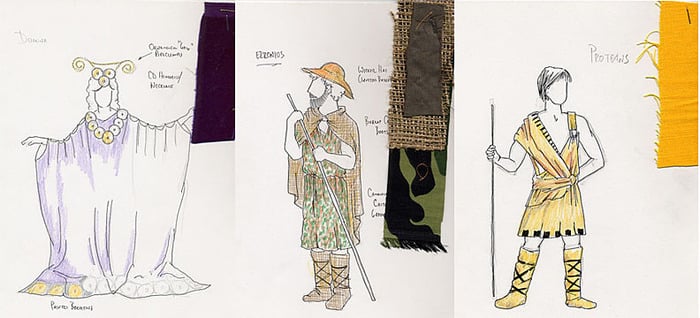

“Costume sketch for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”

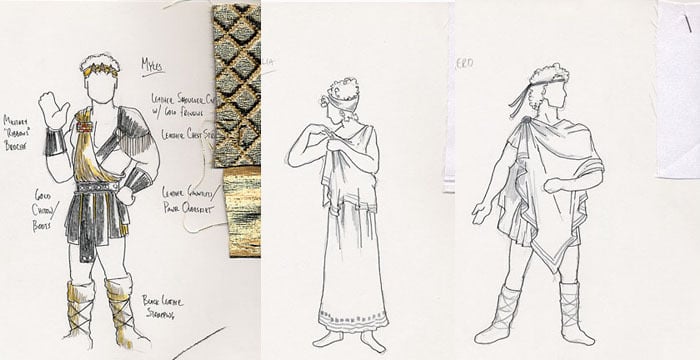

“Costume sketch for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”

“Costume sketch for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”

“Costume sketch for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”

Episode Transcript

Welcome to TFP – The Theatrefolk Podcast – the place to be for drama teachers, drama students, theatre educators everywhere. I’m Lindsay Price, resident playwright for Theatrefolk.

Hello, I hope you’re well. Thanks for listening.

This is Episode 94 and you can catch the links for this episode in the show notes at theatrefolk.com/episode94. Very convenient, I think.

So, today, we’re talking sets which I know nothing about! It’s a big joke here at Theatrefolk that you can do most of our shows with two cubes and, if you took one of the cubes away, no one would really notice – no falling chandeliers, no flies, no mega-sets.

However, set design is really important. You know, there are shows that – well, any shows benefit from a visualization of the theme of a play, right? And I really appreciate set design when it’s done well because it illuminates what you’re watching. It brings the theme to life, right? And bad set design is just so distracting.

So, I saw this play at a very big theatre here in Canada and it was thematically about art and the designer had put – their way of visualizing this was – a huge paintbrush and then just hung it in the air. And, I swear, I spent more time just sort of staring at the paintbrush and wondering about the paintbrush and, “What was the point of the paintbrush, really?” I did more of that than actually focusing on the play.

And I know there are many teachers out there who shy away from big shows, particularly big musicals – it’s big musicals that usually are the ones that have the really mammoth sets – and they shy away from them because of those set demands. And, if you’re one of those, listen in; you’re going to love this podcast.

So, let’s get to it.

Lindsay: Hello, everybody! Welcome to The Theatrefolk Podcast – and I am very excited today to welcome Sean Martin to the podcast.

Hello, Sean!

Sean: Hello!

Lindsay: Tell everybody where in the world you are.

Sean: I am in Mebane, North Carolina; but Montreal, Canada, is home.

Lindsay: Oh! No kidding? A fellow Canadian! Awesome!

Sean: Oh, yeah.

Lindsay: Awesome, awesome, awesome! Oh, I love to hear that! And no one else cares but I think it’s very exciting.

So, this is going to be a really interesting talk. This is something that I know very, very little about. I know that a lot of our listeners, if you’re teachers out there, if you struggle with set design for your musicals, set design in general, you’re going to want to sit right up and get your notepad out and have a talk.

So, first off, let’s talk about what’s your background?

Sean: I actually started in the great big wonderful world of advertising. But I always wanted to be a set designer from about the age of ten when my Aunt Lorraine took me to a touring production of Hello Dolly and we were sitting in the next to last row of the orchestra section and, when the train came on-stage for Put On Your Sunday Clothes, everybody stood up and applauded, and I thought, “Okay. I can do this.”

Lindsay: Isn’t it funny what strikes us? Because, like, for me, when I go, I’m like, I’m so script-focused. And my husband who has also acted, he’s always actor-focused. It’s amazing, all the different pieces that go into a play.

Sean: It is, indeed, and I’ll tell you, you know, it was one of those things that, you know, we all have those little pivotal moments, right? And I went home, fully intending upon going and studying to become a set designer. And my grandfather sat me down and said, “You can’t make a living in the theatre. Of course, you’re not.”

Lindsay: Oh, no!

Sean: And so, I put it off until the age of forty, at which point I decided, “Screw this! You know, I’m either going to do this or I’m not,” and, for the next fifteen years, I had a wonderful career. I designed over 250 productions, including a major world premiere in Spain which was done in a 2,000-year-old Roman theatre in Mérida.

Lindsay: Wow!

Sean: It was the most exciting thing I ever worked on. It was all projection work, but we really worked the architecture that was there so that the projections actually worked with the standing architecture and it was a major high.

Lindsay: I have to tell you, too, even though I know nothing about set design, I know how important it is because theatre is a visual medium, you know? We can say it’s about the text all we want – and, of course, the text is important – but people are sitting in their seats and they are looking. And, if we can find ways to visualize – I guess that’s what it is – visualize what’s going on in the text, you know, and not just have tables and chairs and what-have-you. But, if we can turn it into this thing that really connects with an audience, I think that takes a show to another level.

Sean: Oh, it definitely does. You know, one of the things that always frightens people – especially when they’re doing musicals – is what they perceive to be the amount of expense in the physical production.

Lindsay: Absolutely.

Sean: All of a sudden, everything starts getting stripped out and you find yourself doing everything in front of black velvets and the audience enjoys it but it’s not really the show.

And so, I was approached – this was in 2001 – by a high school in Georgia that wanted to do a production of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. It was going to be their one-act competition play and they were just looking for somebody that could handle the project for them. You know, you think in Forum, “Okay. Simple show; it’s got maybe fifteen people in the cast. It’s only a single set,” until you really start looking at it and then it starts getting a little hairy, especially for something that’s going to have to travel and is only going to be 55 minutes long.

Lindsay: Well, particularly in competition, too, because a vast number of our listeners out there do one-act competitions where you don’t even get time to set up your set. It’s like you and your set are in a little box space, your timer goes, and everything’s got to come on-stage with you.

Sean: That’s right; everything has to be done – at least in Georgia – everything has to be done within 55 minutes.

Lindsay: Yeah.

Sean: The moment it starts and you get your set up and you strip everything off the stage, if you go beyond that, they start tearing off points.

And so, I’m looking at this script and I’m thinking, “Well, now, wait a minute. We’ve got three buildings that are two-stories high and those second stories have to work. I’m not so sure we can do this!”

So, I started talking to the director – wonderful gentleman by the name of Scott Price. The school, by the way, is Washington County High School, and anybody in the Georgia area, I really recommend you guys checking them out because they do amazing productions. We got to talking about this and I said, “Well, Scott, let’s go back and look at this from a conceptual level. You know, what is this play? It’s vaudeville.” I mean, when you really cut through it, that’s what it is. It’s one vaudeville turn after the other. It’s one really one saggy pants joke after another. You know, bring on a pretty girl so they can do their little turn. But it really is an old-fashioned vaudeville musical comedy.

And I said, “Well, you know, there are historical precedents to that, too. You know, you could go back and look at things like, you know, from the Medieval area where plays were performed just in front of simple drops and nobody questioned the fact that the architecture was a little weird and the perspective was a little strange because there were conventions that were built into it that everyone just kind of accepted.” And I said, “You know, really, for that matter, you can go back even further to the days of Plautus,” – the playwright who inspired Forum – and said, “You get in artistic conventions around the vase court that was done at the time where you might have a guy who is up on the second floor of some building and talking to another guy who is on the street level, and the fact that their heads are next to each other doesn’t really matter because, again, there were conventions that were simply accepted.”

And then, all of a sudden, all of this starts to fall together. It’s like, “Well, let’s take all of this and make this into a series of vaudeville drops. Use the convention of the Greek vase so that we just have someone’s head sticking through what’s obviously a painted second floor window. You’re on the second floor.”

Lindsay: Right. You’re just, “Everyone in the audience, you’ve got to believe it.”

Sean: Exactly. You just buy into the illusion and away you go.

Lindsay: For everyone listening, we’re going to have this exact picture in the show notes. I just think it’s fabulous. It’s just so simple!

Sean: It is, and bearing in mind, too, that the budget for their show – for sets and costumes – was $500.

Lindsay: Oh, and that is always a barrier. As you said, for so many people, it’s like, “Oh! I could never do such and such a show because I couldn’t afford it,” and it just takes a little thinking and imagining, doesn’t it?

Sean: Exactly, and we actually extended that into the costume designs as well because, again, you know, you’re talking about an era where, you know, in the days of Roman dress, there were some standardizations. You know, the guys all basically wore one thing; the women all basically wore something else.

But we were able to have with that so that we could take things like Senex, the old man, we took his particular outfit, we do everything in shades of grey houndstooths and grey plaid so he starts looking like a little old man. And then, we would take other characters, the one who’s always out traveling, put him in camo and I’ll do all the things that, again, suggests the fact that this is a man who lives his life on the road.

You haven’t changed the structure. What you have changed are the textures that you use. So, it’s basically the same outfit, but it becomes a completely differnet look.

Lindsay: Right. It’s just all about, well, texture is a great word to use because texture is a really great visual, isn’t it?

Sean: Right, but I’ve got to tell you, my most fun character to design for that thing was Domina, the wife. For the large amount of the play, we put her in what’s called a “chiton” – it’s a Greek outfit that is basically two large square panels that are cut to extend all the way down to the fingertips.

Lindsay: Oh, yes, of course.

Sean: And the way that it’s worn, you have to keep your arms up. So, I mean, she constantly looks like she’s floating across the stage.

Lindsay: And, also, a force.

Sean: Oh, definitely. But the cool thing was, in the last part of the play, you know, she takes on the costume that’s been worn by one of the other characters, she’s disguised herself as the virgin, and she’s now wearing a much simpler outfit and it’s like the gloves have come off and she can be just as abrasive as she wants to and you are going to stay away from her. It was wonderful. The girl who played it originally, Laura McMaster, my god, she was amazing to watch. Absolutely amazing. The transformation was 180-degrees.

Lindsay: Yeah, and I’m sure having those costumes really helped, too.

Sean: It does because it’s helping them settle into the characters. You know, they get to have fun with them. Marcus Lycus – the provider of young ladies of the night as it were – by necessity, was played by a woman. But what we did was we set her up in a costume that was covered with symbols suggesting MasterCard and Visa.

And so, again, it’s these little visual things that you can throw at the audience that not only help them to identify the characters but also get a real fast short-hand on who these people are supposed to be psychologically.

Lindsay: I would say that this would be a great suggestion for teachers out there who are looking to do Shakespeare. You know, if you’ve got an audience who you think, “Oh, we could never do that because my audience won’t understand,” well, make them understand visually, you know. Just like Sean is talking here about how the visuals for the characters and their costumes really gives a great sense of who the characters are. I think you could easily do that with any Shakespeare play because they are so representational, a lot of them.

Sean: Yes, they’re very much archetypes in plays. You know, you very rarely see a transformational character arc – except for people dying.

Lindsay: Which is the big transformation of them all.

Sean: Which is a big transformation, yes, let’s face it.

Lindsay: We also have a picture that we’re going to put up of Fiddler on the Roof. So, talk about that.

Sean: Oh, man. Fiddler was such a fun production. You know, again, you’re looking at a really big show here with a lot of scenery and it was quite frankly much bigger of a show than the stage that Washington County could handle because you’ve got a space that is 30-feet wide, about 25-feet from the lip of the thrust to the back wall and 15-feet in height. No fly space. I mean, this is really a barebones theatre.

And so, again, we said, “Well, let’s talk about concept.” You know, “What’s going on here?” and what clued me in on the approach to this was looking at the script and realizing that these are all based on short stories. And so, I thought, “Okay. They’re stories. Now, when do you tell stories?” You know, you tell stories around the water cooler, you tell stories around the family dinner table, you tell stories around a campfire.

Aha! There we are. You have a bunch of people who are on the road, they’ve had to stop for the night, someone takes out a violin, starts playing, and we are off and running. The whole thing becomes stories generated around a campfire. But then, that require to set up who these people are.

And so, you know, we discussed it a little bit more and I said to Scott, “You know what’s really kind of staring us in the face here is the fact that these people who are on the road are indeed the villagers from Anatevka. They’ve been thrown out of their village, they are accompanied by Russian soldiers, they are on the road, they are tired, they are miserable, they want some entertainment.

And so, it took on this whole almost magic realism because everything that happened in terms of the physical production was brought on-stage by the villagers at the very beginning. If there were chairs, they had them on their backs. If there was a sewing machine, it came out of somebody’s suitcase.

Lindsay: It’s the ultimate trunk show, you know, where everything comes out of something.

Sean: And the other really nice thing about it – and, again, this was working with the one-act version of this play – is that we started it from sunset to sunrise.

Lindsay: How?

Sean: And so, everything in the play travels throughout the night so that, when you get to the wedding sequence where the Russians are coming in and they’re destroying everything, it’s the middle of the night, it’s the darkest moment in their lives, and yeah, it was a really cool production. We had such a great time with that one.

Lindsay: And, again, I think it just really boils down to vision, right? What is the vision for this show and how do we represent it visually?

Sean: The way that I like to look at it is that every play has what I call a key, and you can take that key and unlock the play, and sometimes that key is going to be really elusive, but once you find it, the rest of the play just falls into place, you know? And the key can be almost anything.

When we worked on Guys and Dolls, again, another great big show, and we could not do a great big show. What it came down to was looking at these people and realizing that they are, in some respects, larger than life even within their own environment which would basically mean that, you know, you’ve got a bunch of people who are almost outsized within their own world which immediately leads to, “Okay, what if we have a bunch of recognizable 30s era New York buildings, but they’re on little individual platforms and they can move around to reconfigure the space? And, oh, on the back of them, we can do something else just as interesting,” and we had the entire island of Manhattan there to play with.

You know, it was one of those moments where, if you go in and you look at the script and kind of turn it about 90-degrees and then flip it on its head again, you start to understand how you can take these enormous shows and you can really pull them down to size.

Lindsay: Well, that’s I think what quite a lot of particularly high schools miss is that they see big show which would be really awesome for their students to perform – absolutely – and they think, when it comes to sets and costumes and all of that, “I have to mimic what was on Broadway or what was on regionals,” and that is an impossible bar to reach, isn’t it?

Sean: Oh, yeah, it really is. I mean, even these touring companies are multi-million-dollar productions even if they’re just faint knockoffs of the Broadway originals. It’s really kind of frightening. And, you know, this is kind of leading to another thing, a little personal thing for me.

One of the things that I collect are 1920s through 1940s era what they used to call “juvenile apparatus.” These were original musicals that were written specifically for middle and high schools.

Lindsay: No!

Sean: Serious!

Lindsay: 1920s?

Sean: Yeah, they actually started around 1900. The earliest one in my collection is something called The Pennant – it’s from 1902. The last one that I have is from 1950 and it’s a really bad adaptation of The Merry Widow.

Lindsay: And you know they’re specifically for schools?

Sean: Oh, yes, they were designed specifically for schools.

Lindsay: Holy smokes!

Sean: You can still find them occasionally on eBay and they’re fascinating, but the really cool thing about them was that you just got a script. You had no idea what it was going to look like because, you know, the thing had never been performed before – at least not in your experience. It wasn’t like it was a Broadway show.

Lindsay: So, it was your imagination that built it.

Sean: Exactly. You had to create the whole thing, whole cloth, and I’ve seen photographs of some of the productions that were done – mostly in the 30s and 40s – and they’re absolutely fascinating. You have costumes made out of crepe paper for crying out loud because it was Depression Era. There are whole books that are written on how to produce these things literally on twenty cents. They’re really an amazing little art form and I think it’s sad that we’ve lost those in some respects in this rush to do Annie and Grease to distraction.

Lindsay: Well, that’s where things are going, and not only that, it’s that schools are more and more wanting to do these well-known names. They use them as fund-raisers. People won’t come unless there’s a well-known name. There is a wealth of wonderful small musicals with no cache that get pushed to the wayside because they don’t have this name. And then, there’s just this notion of bigger is better. And then, budget-wise, it just becomes an astronomical expense and a stress expense, too.

And I really do think, I think of so many teachers who I know who just don’t have, this is not in their wheelhouse. They get thrown into these situations in schools where they have maybe an acting background and, all of a sudden, they’re a one-man band and they don’t have the sets and the things. And then, you’re right; they end up doing it in black box.

Sean: Right, which is not to be completely dismissed.

Lindsay: Oh, all my plays are black box. Every play that I write, you know, it’s literally you could do it with two cubes and, if you took away one cube, no one would miss it, you know.

Sean: Well, there we go.

You know, there are some shows that really will work well in front of black drapes – there’s no question about it. It’s just you have to be extremely careful about what you’re putting in front of those black drapes that will make it seem somewhat larger than life.

Lindsay: And I think it’s really important that, if you’re going to do these musicals, why not have it? Well, actually, any play… you should have a vision and you should find a way to represent it visually.

Sean: Yes, because that’s part of educating these kids for theatre.

Lindsay: Cool. Okay. So, as we wrap up, let’s talk about some advice that you would give to teachers in terms of putting together a set design in terms of cutting down these big musical down to size?

Sean: I think the biggest thing that I would emphasize on them is to think conceptually. Pretend that no one has ever done the show before except you and really look at the script the same way that you would look at, let’s say, you know, a midterm paper by one of your students. What is this play about? When does it take place? What happens if you, for example, change all the guy and girl roles to the opposite gender? What is the message of the play?

And then, take all these really kind of basic questions and then just start building it one little piece at a time. If you’re going to do Phantom of the Opera, don’t look at it as, “Oh, my god, there is a chandelier and there are these mock operas that have to be done.” Again, take it down to its most essential. What is the play about? It’s about a man who plays the organ underneath the opera house. Start from that point and build out, but build out slowly so that you never forget what the core is that you’re trying to convey to your audience.

Lindsay: Absolutely. Absolutely.

What about a couple for those teachers who are feeling inept with their technical skills? What about a couple of technical tips for set building and set design?

Sean: Oh, man. You’re really talking to the wrong person.

Lindsay: Oh, okay!

Sean: You put power tools in my hand and it becomes a dangerous situation.

Lindsay: Cool. Okay. So, let’s step back. So, what do you put in place to have built that a teacher could do?

Sean: Okay. Well, see, I try to design with an eye for simple construction.

For example, everything in Forum is basically done with three small platforms – they’re all two-by-four platforms, some PVC piping from Home Depot, and three large pieces of canvas.

Lindsay: See, that’s exactly what we want to hear, right? PVC and some canvas.

Sean: Exactly, and that’s all you need, you know? I mean, you can do the whole show with just that. It’s what you do with it that makes the difference. You know, all the stuff for Fiddler was just basically cut from quarter-inch plywood painted black. It was just the lighting that made it work and that’s something else right there. Never underestimate the power of your lighting grid. You may only have three strips up there, but by golly, you can make those things really sing and dance if you think about it.

Lindsay: Awesome. Okay!

This has been really great. I know how much the musical is prevalent in high schools and I know too how many teachers are like, “No, I could never do it because I could never pull off the adequate set requirements,” and about how, you know what, it’s really possible, isn’t it?

Sean: It really is, and actually – let me just sort of throw the offer out there – I do all of this stuff on a pro bono basis. I have a job that pays me very well so I can definitely afford to volunteer my time on these things. If anybody has a question about how to approach a show, drop me a line. We will put my email address in the show notes.

Lindsay: You bet.

Sean: And, yeah, just drop me a line and let’s see what we can do to make it work for you.

Lindsay: That is really awesome. Thank you so much, Sean! And I hope some people take you up on it because I really love the two pictures that we’re going to throw up there for Fiddler and also for Forum. Conceptually, I just think they really go to the heart of what I think theatre should be – that theatrical experience that’s not a representation of “this is a real building and this is a real table and chairs” – it’s something a little more.

Sean: Well, thank you. I’m glad you like them.

Lindsay: Awesome. Have a great day!

Sean: Okay. You do the same. Buh-bye!

Thanks, Sean! Great stuff!

Okay. So, you can get the show notes for this episode at theatrefolk.com/episode94 and make sure you go there and see the pictures of the two shows that we talked about – Fiddler on the Roof and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. I think you’ll be amazed at just how simple and yet effective these sets both are.

So, before we go, let’s do some THEATREFOLK NEWS.

Since we’re talking tech, I think that it’s very appropriate that we talk PTT – the Practical Technical Theatre DVD series. So, we distribute this series of instructional DVDs and they are perfect for teachers who feel more at home with a prompt book than with a hammer, right? They’re technical teaching tools and each and every one is a visual textbook with assignments and lesson plans, assessment sheets, rubrics, everything you need. It is a full curriculum for any tech theatre classroom.

They are all hosted by Bob and Marti Fowler. We love these guys and they are, of course, master theatre educators. They both spent a long time teaching in the St. Louis area and these DVDs, they’re going to turn your students into valuable theatre technicians who know what to do and how to do it.

So, there’s ten DVDs in total and they cover topics such as intro to tech theatre, set construction and safety, lighting, sound, set design – that’s just to name a few.

So, head on over to our resource page on theatrefolk.com and we’ll also put the direct link in the show notes for theatrefolk.com/episode94.

Finally, where, oh, where can you find this wonderful podcast?

Well, we post new episodes every Wednesday at theatrefolk.com and on our Facebook page and Twitter. You can find us on YouTube.com/Theatrefolk. You can find us on the Stitcher app and you can subscribe to TFP on iTunes. All you have to do is search on the word “Theatrefolk.”

And that’s where we’re going to end. Take care, my friends. Take care.

Music credit:”Ave” by Alex (feat. Morusque) is licensed under a Creative Commons license.